Physical and mental health prevention in the context of a pandemic

The current pandemic highlights just how important prevention is in the health network and in dealing with the challenges facing various professionals. The first waves led to many findings and now it is absolutely essential to go further and collectively develop a true culture of prevention. Many tools and recommendations were put forward and so now we just have to implement them! Let’s act now!

Your rights and obligations

If you contracted COVID-19 at work, for the 14 full days following the onset of your disability, you are entitled to 90% of your net salary for each day or part day when you would have normally worked, including the overtime hours scheduled, as applicable, and also to all of the premiums, including inconvenience premiums, and lump sums that you were entitled to at the time you stopped working (AIAOD, s. 60).

The employer can obtain a reimbursement from the CNESST for the income replacement indemnities paid to you during the first 14 days. The employer must fill out the Employer’s Notice and Reimbursement Claim form and send it to the CNESST (AIAOD, s. 268). The employer must give you a filled-out and signed copy (AIAOD, s. 269). Please note that even though the employer will complete this process, you are still obliged to fill out the Worker’s Claim form. It is the worker’s obligation to submit their own claim to the CNESST (AIAOD, s. 270) by filling out the Worker’s Claim form.

For all claims received on or after March 1, 2023, the CNESST requires that you consult a healthcare professional to obtain a medical certificate confirming the COVID-19 diagnosis.

COVID-19 – Know your rights and obligations

Even if the employer compensates you after your injury, it is absolutely crucial that you quickly fill out the Worker’s Claim form and submit it to the CNESST. It is even more important right now since knowledge of the “post-COVID syndrome” is still in its very early stages. The disease could have unsuspected long-term effects. As such, it is crucial that you report your employment injury to the CNESST as early as possible so that you are eligible for any indemnities in case of a relapse or worsening of the condition, as well as for all the benefits provided for in the law.

Emerging dominant variants

En date du mois de September 2023, le variant actuellement dominant est le EG.5.1 (Eris). The latter is paired with the XBB.1.5 variant, which is currently in decline.

At the beginning of September 2023, nearly a quarter of infections in Canada are caused by the EG.5.1 (Eris) variant. Although it is the most contagious to date, it does not appear to be associated with an increase in the severity of symptoms.

Moreover, the WHO is closely monitoring a new sub-variant, BA.2.86. This variant has nearly 30 mutations in the spike protein. This variant appeared in British Columbia, Canada, at the end of August.

Vaccination is still the best way to protect oneself. Vaccines continue to be a good way to protect against the most serious symptoms of the illness. The high vaccination rate is one of the factors that explains the stabilization of hospitalized cases.

You can follow the daily evolution of the COVID-19-related situation on the website here.

Vaccination

The right to the most recent vaccine protection is a priority for healthcare professionals.

Health Canada approved a new vaccine targeting XBB.1.5 in September 2023. Approval is also pending for a new Pfizer vaccine. These vaccines will be more effective than their predecessors in targeting circulating variants, even though they do not specifically target the emerging BA.2.86 variant.

With a new vaccination campaign on the horizon, it is imperative for employers and the government to ensure that healthcare professionals have quick and easy access to vaccination.

Vaccination and occupational health and safety

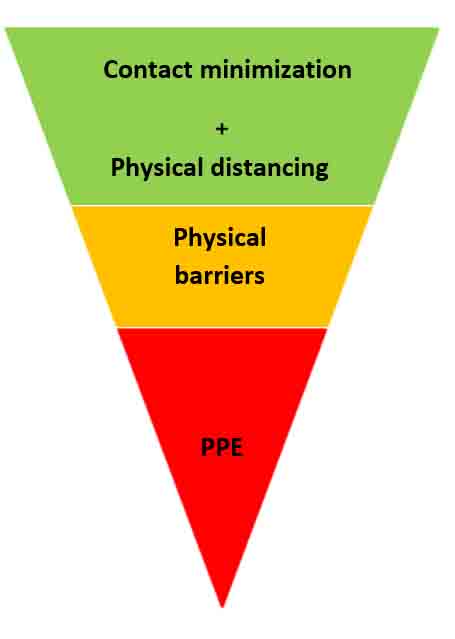

The Federation reminds its members that vaccination is the most effective means of prevention when combined with the other means of prevention needed to prevent OHS risks.

The Federation demands that the government make an extra effort to offer vaccination in the workplace, so as to avoid encroaching on the healthcare professionals’ time off.

Healthcare professionals have a front-line role in promoting vaccination. In the field, healthcare professionals are the main ambassadors for vaccination and other public health measures among the general public.

Vaccination is a public health measure, but also a means of prevention in occupational health and safety. In this respect, vaccination is one of a series of other equally essential means of prevention. For a preventive measure to be fully effective, it must be rooted in free and conscious adherence. Vaccination campaigns must not minimize the importance of other means of prevention essential for our healthcare professionals, which means implementing the hierarchy of preventive risk methods in the workplace.

In addition to vaccination, it is essential to continue guaranteeing access to the personal protective equipment required by the CNESST or deemed necessary by the healthcare professionals in the field.

What are the known benefits of vaccination

- Scientific data still show that vaccination is effective against the virus and its variants.

- Vaccinated people who contract COVID-19 have a lower risk of transmitting the virus.

- Vaccination is therefore highly effective against serious forms of the disease. However, no vaccines provide 100% protection. COVID-19 vaccines are no exception. That is why we must continue to use all OHS preventive methods, even after getting a booster shot.

Are vaccines safe?

- While COVID-19 vaccines were developed rapidly, all steps were taken to ensure their safety. The massive investments in research helped to simultaneously complete several steps of vaccine development.

- In Canada, COVID-19 vaccines underwent the same analysis by Health Canada as all other vaccines. Furthermore, in Canada and Quebec, there is active monitoring of unidentified adverse side effects before vaccines are marketed.

- Like all vaccines, COVID-19 vaccines have adverse side effects, but they are monitored closely. That said, the benefits of vaccination as protection far outweigh the inconveniences.

- Overall, the side effects associated with the booster shots are similar to those of the first and second doses.

Sources:

https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-002830/https://sante-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/securite-vaccins/

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety.html

Does vaccination pose a risk to women who are pregnant or breastfeeding?

- There is a higher risk of complications from COVID-19 for pregnant women. Also, contracting COVID-19 while pregnant poses higher risks for the unborn child, such as prematurity.

- There is evidence-based data that mRNA vaccines are safe for pregnant women. Moreover, the messenger RNA in the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines quickly destroys itself in cells and, consequently, does not pose any risks to an unborn child.

- Available data also indicates that there does not appear to be associated risks for breastfeeding following an mRNA vaccination.

- Given the available data, the comité d’immunisation du Québec (CIQ) and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) recommend vaccination for pregnant women.

- The Federations maintain that the assignment of pregnant workers, even if they are adequately vaccinated, must be done in conjunction with the principles of precaution and in compliance with the INSPQ’s recommendations

Sources:

https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-002830/

https://www.fiqsante.qc.ca/dossiers/pandemie/retrait-preventif/

How to react to (anti-vax) misinformation about vaccination?

- There is a lot of misinformation out there and it is important to think critically and protect oneself. There is an abundance of information about COVID-19 and we naturally need to stay up to date on and understand how the situation is changing.

- To be properly informed, it is essential to question information sources and to verify if other media sources confirm the information. Furthermore, it is very important to distinguish facts from opinions. Facts can be proven, verified and do not depend on the author.

The biological risk

Advocate for and demand better protection

The lack of protective equipment have been at the heart of the healthcare professionals’ concerns. This issue has created doubt about the ability of healthcare professionals to work in a way that is safe for themselves and their patients. It has undermined trust in authorities and their credibility.

From the beginning of the pandemic, the FIQ alerted the government to the risks linked to poor protection of healthcare professionals. Right from the start, it demanded an organization of the provincial production capacity of protective equipment according to the precautionary principle so that supply problems are quickly resolved. The FIQ and its unions participated in putting the public health recommendations into practice while focusing on good practices in infection prevention and control (IPC). Moreover, the FIQ warned that the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) can never justify a reduction in the protection of healthcare professionals.

Personal protective equipment

For the Federations and their affiliated unions the institutions should implement the following infection prevention and control measures to ensure maximum protection for healthcare professionals in the field.

Protective measures to apply

- The CNESST confirmed that it is necessary for healthcare professionals who work with patients who do not meet the criteria listed in the section “Usager à faible risque pour la COVID” (low-risk patient for COVID) from the linked table to wear an N95 mask:

- https://www.cnesst.gouv.qc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/masques-minimalement-requis-milieux-de-soins_0.pdfThe FIQ does not recommend reusing masks, using expired masks, or using disinfected disposable masks.

Checklist for personal protective equipment against COVID-19

- N95 type RPD or better.

- Single-use eye protection (face shield or protective goggles).

- Unsterile disposable single-use long-sleeve gown.

- Unsterile single-use gloves.

Using N95 masks and surgical masks

Despite our recommendations on using N95s, please note that wearing an N95 mask for an extended period of time has certain risks you should be aware of. The ASSTSAS created this document outlining the risks.

The FIQ recommends the following measures if a medical mask (ASTM level 2 and 3) is used in a cold zone and/or in the absence of any confirmed or suspected cases.

- That the mask be properly fitted.

- For optimal mask effectiveness, a healthcare professional and patient must be facing one another head on (during a procedure when a patient is to the side of a professional, droplets and aerosol particles can reach the healthcare professional on the side of their face).

- It is important to change the mask when it becomes damp because it will lose its protective properties, unless it is waterproof.

It is important to continue to be vigilant when an employer bases their positions on the recommendations of the INSPQ.

We would like to reiterate that the CNESST maintains its decision to apply the precautionary principle, in particular with the obligation to wear an N95 respiratory protective device with patients who have confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 in a warm or hot zone, regardless of vaccinations and alert levels. We would also like to reiterate that a level 2 ASTM medical mask does not provide sufficient protection against the airborne transmission of COVID-19. Remember that the CNESST’s requirements must be applied and take precedence over all INSPQ and MSSS recommendations.

Basic universal practices applicable to COVID-19

Systematic application of basic practices for every patient is the rule to prevent the transmission of infections. The FIQ recommends the following practices in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Information about PPEs

- RPD (respiratory protective device): must have undergone a Fit Test, be well adjusted and be used at the very least following the CNESST’s instructions in warm and/or hot zones in the presence of a confirmed or suspected case.

- Eye protection: Prescription glasses are not considered adequate protection. Eye protection, protective goggles or a face shield that covers the face down to the chin can be used for a full work day, subject to the healthcare professional’s clinical judgement regarding possible contamination of the eye protection.

- Gown: wear a waterproof gown if there is a risk of coming into contact with bodily fluids (e.g.: vomit, severe cases). It is recommended that you change gowns between each patient.

- Gloves: ensure they are well fitted and cover the wrists.

- Do not touch your eyes, nose or mouth if your hands are potentially contaminated.

- Systematically remove the gown and gloves when leaving the examination room.

- Practice good hand hygiene before putting on PPE and after removing it, in compliance with the IPAC. It is important to remove the protective material in a way that prevents contamination and then to properly wash and dry your hands (a damp environment can be a factor of contamination).

- Use disposable instruments, but if that’s not possible, wash and disinfect the material between each patient. Dispose of PPE according to the IPAC procedure.

- Whenever possible, patients who require AGMPs be given care in individual, closed negative pressure rooms or in closed properly ventilated rooms with an antechamber.

The IPC team

During the Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) outbreak in 2004, the Comité sur les infections nosocomiales du Québec recommended a standard ratio[1] for ensuring an effective IPC intervention.

Nurse clinicians specialized in IPC are the expert resources in IPC outside of the medical body. The FIQ hopes that the current pandemic is an electroshock so that nurse ratios specialized in IPC are introduced in all care settings.

Union action in IPC

The healthcare professionals are entitled to working conditions that respect their health and safety, and protect against the dangers linked to biological substances. The employer must take all necessary measures to ensure this protection.

For its part, the union is a major player in IPC because its role is, among others, to ensure members’ rights are defended, improve their working conditions and protect their health. If you see a problem linked to IPC in your institution, tell your union as soon as possible. They can intervene with the employer so that corrective measures are taken.

Work environment and organization of work

As of April 2020, the health authorities began setting up complete medical structures fully dedicated to COVID-19 to separate COVID-19 patients from others.

On one hand, the idea behind this organization of care was to take care of patients with COVID‑19 in a closed circuit, without any exchange of patients or staff between outbreak and non-contaminated areas. On the other hand, this organization of work was intended to ensure that health institutions did not become places of propagation. It is an efficient organization of care method, designed in such a way as to apply all elements of the plan in a complementary way.

Ensure that organization of care allows for a health care corridor. Be alert and demand that closed circuit care is applied. As the CNESST guide indicates, “Adaptations must be made to limit the risk of transmission when physical distancing principles cannot be respected::•

- Use of technological means (telework, virtual meetings);

- If possible, physical barriers (e.g.: solid partition) installed between the different workstations that are too close or cannot be spaced out;

- If possible, schedules are reorganized to avoid the simultaneous arrival and departure of several workers when this situation causes congestion;

- If possible, workers are assigned to a single workplace (one facility, and ideally one floor or one wing) to avoid a greater number of interactions ;

- It is recommended to create clusters of confirmed cases or room isolation depending on the setting. Refer to the INSPQ COVID-19 fact sheet: Mesures pour la gestion des cas et des contacts dans les centres d’hébergement et de soins de longue durée pour aînés.” (Measures for managing cases and contacts residential and long-term care centres for seniors)

The FIQ recommends going further and ensuring that your work team is stable and composed of colleagues assigned to a specific clientele.

Ventilation measures

The CNESST has issued some recommendations on the maintenance and operation of the ventilation system. It contains the following information:

- Operate ventilation systems optimally during operating hours;

- Increase the supply of fresh outdoor air to dilute airborne contaminants either through mechanical ventilation or by opening windows;

- If possible, increase filtration in areas with more occupants or by evacuating the air to the outside;

- If necessary, promote the use of an air purification system in the rooms; if necessary, ensure that the air exhaust system in the bathrooms is in working order and functioning optimally;

- If possible, use negative pressure ventilation in the hot (hazardous) zone so as not to contaminate other areas of the facility.

The FIQ also recommends:

- Operating the ventilation system continuously, reducing its intensity if necessary, even outside operating hours

- Being careful when opening windows so as not to create positive pressure in high-risk areas or bathrooms. This would have the effect of creating an air flow from risk areas to healthy areas.

- Checking the maintenance log of the ventilation system to ensure that the work has been completed within the recommended time frame. If necessary, carry out emergency cleaning and maintenance work.

- Using HEPA or MERV13 or higher filters to ensure good filtration efficiency.

- Checking whether the filters have exceeded their service life. If so, carry out emergency replacement work.

- If the use of air purifiers in rooms is envisaged, it must be ensured that they do not generate a flow of stale air to healthy areas and that the necessary maintenance can be carried out on the unit. The suitability of such a unit should be assessed by a ventilation expert before installation.

Heat in institutions

Discomfort and heat stress are serious issues in several of our work environments and the health crisis has major impacts on healthcare professionals’ work: understaffed teams, high workload, multiple layers of personal protective equipment, etc. All this adds extra challenges in hot weather. We propose a series of ways to mitigate or resolve the hazard heat represents in our work environments. The best way to implement these methods is to have healthcare professionals take collective action themselves. Contact your FIQ union to take collective action.

Pandemic

The aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has been well-documented. During the summer, it is common to open windows to allow for natural ventilation when the outside temperature is cooler than the inside temperature. However, it is recommended to always first check with IPAC if this type of practice can pose risks given the currents of air generated and the aerosol transmission of the virus. One must also first check with IPAC before installing ventilators, air conditioning and dehumidifiers

Additional personal protective equipment accentuates the hazards related to heat stress. Wearing an extra layer of clothing reduces a body’s ability to regulate its temperature. Furthermore, wearing PPE for a long time can make hydration difficult. In this context, we believe it is the employer’s responsibility to organize work in a way that ensures healthcare professionals’ safety. For example, by increasing the number of breaks, giving them enough time to hydrate, and reducing the workload.

What employers should plan to minimize heat-related risks and discomfort

Risk identification and reduction always starts with eliminating them at the source and then moves onto individual methods. Addressing heat-related risks is no exception.

At the source:

- In compliance with IPAC rules, whenever possible, air condition the workplace or a section of it. (Central air conditioning, portable air conditioner, fan).

- Plan ways to limit sun exposure in the workplace and leave windows closed when the outside temperature is hotter than the inside one.

- Limit the use of heat-emitting devices or equipment.

Administrative measures:

From the union’s point of view, it is important to ensure that the employer truly plans work organization so that employees can work safely in hot weather.

- The employer should take the necessary steps to inform and train healthcare professionals on how to deal with risks related to heat, symptoms associated with heat stroke, and strategies to use to eliminate or reduce these risks.

- The employer should provide access to a cool, aired place where healthcare professionals can take breaks in a restful and temperate environment.

- The employer should review the organization of work to allow healthcare professionals to take mini breaks and extra breaks in hotter weather. According to a survey conducted by the ASSTSAS, 83% of surveyed institutions deplored the work-rest cycle measures.

- The employer should review the organization of work to reduce the pace and intensity of work. For example, by scheduling the most demanding duties for the coolest times of day or by increasing staffing on work teams (adding healthcare professionals to cover breaks, for example, or adding auxiliary staff). Once again, 83% of institutions say they lighten the workload.

- The employer must ensure that healthcare professionals have access to cold water at all times and must organize work so that they can hydrate as often as necessary. It’s a delicate issue, especially when there is a work overload (lack of time to hydrate), and staff are wearing PPE. In terms of PPE, the employer must be sure to adequately train healthcare professionals on how to hydrate themselves in a safe way so that they don’t contaminate themselves.

Individual measures:

- The employer can provide healthcare professionals with cooling PPE (cooling headbands or neck wraps). These PPE should only be for personal use. They should not be shared between healthcare professionals.

- Make accommodations for healthcare professionals who are more vulnerable to heat due to a particular medical or personal situation. These personal factors could include taking certain medication, previous heat stroke incidents, working overtime or mandatory overtime, or a specific physical or medical condition, etc.

- The discomfort associated with N95 masks can be exacerbated by heat. It is possible to evaluate auxiliary strategies to make these masks more comfortable. For example, by adding adhesive lines under the mask (if they don’t compromise the airtightness) or using certain hydrating creams

What healthcare professionals should plan for

To drink 250 ml of cool water every 20 minutes. Even more if you meet certain criteria listed in the charter proposed by the CNESST. Never drink more than 1.5 L per hour.

- Try to eat light, fresh meals.

- Talk with your colleagues and contact your FIQ union if the employer is not taking proper measures to mitigate the discomfort or heat stress. Help the employer and union to identify the hazards and ways to eliminate or mitigate them.

- Immediately notify an employer representative and immediately stop working if you have any symptoms of heat stroke or that warn of heat stroke. (No sweating, hot and dry skin, incoherent speech, loss of balance, drowsiness, nausea, loss of consciousness, convulsions). If you observe these symptoms in a colleague, immediately inform your immediate supervisor.

Important

- The CNESST proposes a method to measure the heat in a work environment and how to adapt the work based on the hazard. Based on the level of heat and intensity of work, the CNESST’s tool proposes a hydration and rest frequency. The level of heat and actions must take into account:

- The relative humidity: The relative humidity in a healthcare building should generally be between 30% to 60%.

- Personal protective equipment being worn: Equipment that is airtight or keeps sweat trapped inside increases heat stress (gowns, gloves, masks, face shields).

- Efforts made: In general, working sitting down or standing up while performing light tasks (e.g., taking vital signs) is considered light work. Working on your feet at a steady pace while performing more strenuous tasks (e.g., hygiene care or patient mobilization) is medium work.

When you work in an environment that reaches a certain temperature, you must follow the CNESST’s recommendations and the employer must allow you to do so.[8] If there is a problem, consult your union immediately.

To use the CNESST’s heat scale, the temperature must be taken:

- With a thermometer and a hygrometer.

- The union must participate in taking the temperature.

- At a frequency agreed upon with the union.

- The result must be recorded in a register.

Physical risks

La violence

Another result of the increase in physical risks due to COVID-19 is the rise in workplace violence. Workplace violence is intrinsically linked to a work overload and psychosocial risk factors. As reported by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec, studies have shown a rise in violence against women during periods of crisis or public health crises in society in general[1]. Studies also tend to establish a link between the context of the pandemic and a rise in conjugal violence.

Rising risk factors related to violence in society is mirrored in the workplace. Moreover, the Association paritaire pour la santé et la sécurité du travail du secteur affaires sociales produced a checklist called COVID‑19 – Intervenir en situation de violence (in French only) to prepare health care workers for situations when a user, through his violent or threatening behaviour, is a danger for his safety or that of others. The Association paritaire pour la santé et la sécurité du travail, secteur Administration provinciale also produced a document reminding employers about best practices in violence prevention in client services.

Workplace violence has a multifactorial dimension. It cannot be reduced to the link between employees and users alone. Moreover, this is what the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health concluded in its report, Violence facing health care workers in Canada published in June 2019. In the words of Ms. Margaret Keith, the Committee wrote

« The culture of silence around the issue of violence is a major barrier to acknowledging its existence and consequently, addressing it. However, although the public has been kept in the dark about this issue, it is not a problem that is unknown within the health care community »

If you are a victim of workplace assault or violence

- Inform your immediate superior.

- Fill out an incident/accident form AH-223.

- Contact your union team.

- Fill out a work accident form even if there is no obvious injury.

- Contact your family doctor.

List of resources for obtaining help or support

Provincial agencies

- Centre d’aide pour les victimes d’actes criminels (CAVACS) 1 866 LE CAVAC – 1 866 532-2822

- Groupe d’aide et d’information sur le harcèlement sexuel au travail de la province de Québec – Tél. : 514 526-0789

- Regroupement québécois des CALACS (Centre d’aide et de lutte contre les agressions à caractère sexuel) – Montréal : 514 529-5252 – Extérieur de Montréal : 1 877 717-5252

Agencies working with victims of assault and conjugal violence

- Ligne téléphonique d’écoute, d’information et de référence destiné⦁ e⦁ aux victimes d’agression sexuelle, à leurs proches, ainsi qu’aux intervenants – 1 888 933-9007

- Regroupement québécois des centres d’aide et de lutte contre les agressions à caractère sexuel (CALACS) – Contactez le regroupement de votre région

- Le réseau des centres d’aides aux victimes d’actes criminels (CAVAC) 1 866 LE CAVAC – 1 866 532-2822

- Mouvement contre le viol et l’inceste – Tél. : 514 278-9383

- Trêve pour Elles – Tél. : 514 251-0323

- Centre pour les victimes d’agression sexuelle de Montréal. Ligne-ressource sans frais provinciale 24 heures/7 jours – Partout au Québec, composez le : 1 888 933-9007 – Pour la région de Montréal, composez le : 514 933-9007

- Clinique pour victimes d’agression sexuelle. Hôpital Notre-Dame, 1560, rue Sherbrooke Est, Montréal, QC H2L 4M1 – Demandez à parler à l’intervenant(e) de garde : Tél. : 514 413-8777

- Centre de prévention des agressions de Montréal – Tél. : 514 284-1212

- Centre d’amitié autochtone de Montréal – Tél. : 514 499-1854

- Directeur des poursuites criminelles et pénales (DPCP). Ligne téléphonique destinée à renseigner les personnes victimes de violences sexuelles qui envisagent de déposer une plainte auprès des policiers – gratuit et confidentiel – 1 877 547-DPCP (3727)

- Juripop – Services juridiques gratuits et confidentiels

- Centre d’expertise Marie-Vincent – Courriel : ⦁ info@ceasmv.ca

- Centre de ressources et d’intervention pour hommes abusés sexuellement durant leur enfance (CRIPHASE) – Tél. : 514 529-5567

- Table de concertation sur les agressions à caractère sexuel de Montréal. Guide bleu d’information disponible à l’intention des victimes d’agression sexuelle

- Table de concertation en violence conjugale de Montréal. SOS VIOLENCE CONJUGALE – 1 800 363-9010

- Tel-jeunes – 1 800 263-2266

- Clinique de consultation conjugale et familiale Poitras-Wright et Côté – Tél. : 450 6700468

Clinique universitaire de psychologie, Université de Montréal, Département de psychologie – Tél. : 514 343-7725

In the midst of the pandemic, the Ministry of Health and Social Services contacted the Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS) to obtain a réponse rapide (quick response) on the measures to put in place to counteract the harmful effects of the pandemic on the mental health of network personnel. Among the INESSS findings are the personnel’s concerns and fears related to the context of the pandemic, the mental distress and mental health problems.

A few elements taken from the INESSS document are:

What concerns can the healthcare professionals have?

- Concerns related to their physical and mental capacities.

- Concerns related to the health of their loved ones and risks of contamination.

- Fears about contracting the disease or dying.

What are the mental health problems in the context of a pandemic?

- Fatigue and stress.

- Aggravation of pre-existing physical or mental health problems.

- Increase in alcohol consumption and other mood-altering substances.

- Moral suffering and psychological distress related to clinical decisions to prioritize access to care.

- Sleep, concentration and appetite disorders.

- Anxiety and depression.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Some of you are possibly at higher risk to experience psychological distress or mental health problems, due to personal or family characteristics:

- If you feel pressure from loved ones to leave the profession.

- If you have difficulty balancing professional and family requirements.

- If there are members of your family with COVID-19, suspected to have it or seriously ill.

- If you experienced grief recently.

- If you have a chronic disease or a history of mental disorders.

Moreover, health care personnel would be more likely to experience psychological distress or mental health problems, because of certain characteristics specific to this sector of activity:

- The personnel with direst exposure to the suffering of infected people and must deal with the users’ anxiety or concerns.

- The one working in a high-risk setting.

- The one working in a geographic epicentre.

Harmful effects on health

Before the pandemic, being exposed to one or several psychosocial risk factors involved

- 4 to 4 times greater risk of work accidents.

- Twice the risk of psychological distress.

- 5 to 4 times greater risk of musculoskeletal disorders.

- 2 to 2.5 times greater risk of cardiovascular disease.

- 5 times greater risk of cerebral vascular accidents (CVA).

Preventing a single case of a mental health problem could reduce costs:

- Absenteeism: $18,000 (or 65 workdays on average).

- Presenteeism: the estimated cost is almost twice the cost of absenteeism.

Presenteeism is a phenomenon characterized by employees’ presence at their workstation, even if they have symptoms (e.g. fatigue and difficulties concentrating) or a disease that should cause them to take time off work and rest. Why does presenteeism generate costs? Presenteeism may result in lower levels of productivity and risk of errors, breakage or work accidents.

Psychosocial risk factors at work

The psychosocial risk factors at work are defined as factors related to organization of work, management practices, employment conditions and social relations, that increase the likelihood of adverse effects on physical and psychological health of the people exposed (INSPQ, 2016).

The main psychosocial risk factors at work recognized in the scientific literature are:

- The work load

- Social support from the superior and colleagues

- Decision-making autonomy

- Recognition

How do psychosocial risk factors act?

In its document on psychosocial risk factors, the Institut national de recherche et de sécurité pour la prévention des accidents du travail et des maladies professionnelles (INRS), a French scientific body, explained that:

(…) according to work situations, the psychosocial risk factors may compensate (for example higher requirements, but good quality social support) or, on the other hand, strengthen itself (for example higher requirements and lack of recognition of efforts made). Different studies show the more “toxic” they are on health when :

- They are part of the long term

The sustained psychological risk factors may in fact create a stage of chronic stress that that represents a health risk. - They are sudden

Sudden psychosocial risk factors are more difficult to deal with. - They are numerous

An accumulation of risk factors is a compounding factor. - They are incompatible

The coexistence of certain “aggravating” factors particularly affects health, for example a high demand for productivity and little room for manoeuver.

Even though the INSPQ refers to 4 main psychosocial risk factors, this number is not exhaustive. For example, the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace refers to 13 psychosocial risk factors. For its part, in its publication Mental Health: Is your workplace safe? “Mental Health – Is your workplace safe? ”, the FIQ referred to 8 psychosocial protective factors more representative of the healthcare professionals’ work reality.

Preventive measures for employers

The Federation wants to take advantage of the 2020 OHS Week to inform and equip the healthcare professionals. However, because occupational health and safety is everyone’s business, it’s a good idea to repeat the recommandations de l’INSPQ à l’intention des employeurs (INSPQ recommendations for employers – in French only) on the psychosocial risk factors in the context of a pandemic. On reading these recommendations, the healthcare professionals can also verify the employer properly applies them in their work environment

Presence of psychosocial risk factors at work

A few examples of factors that could contribute to the emergence of psychosocial risk factors for healthcare professionals are:

Workload

With respect to workload, are healthcare professionals, for example, subject to:

- A heavier workload, pressure to pick up the work not done.

- Long work hours (e.g. no breaks, mandatory overtime).

- A staff shortage.

- Poorly defined work mandates, tasks or instructions or subject to many interpretations or changes.

- A lack of tools necessary to do a good job (e.g. personal protective equipment).

- A lack of training for the tasks she is asked to do when resources are shuffled.

- Greater complexity of work related to respecting the instructions for protection (e.g. distancing, use of personal protective equipment).

- A feeling of not being able to do quality work.

- Ways of doing things that clash with their personal or professional values.

- Emotional traumas (e.g. agonizing care decisions, patients’ deaths).

- Inappropriate behaviour by patients or their loved ones.

- Fear of being contaminated by COVID-19 and contaminating their loved ones

- Difficulty in balancing work, family, and personal responsibilities (e.g. telework, daycare).

Social support from superiors

Is social support from superiors currently marked by:

- A lack of availability to provide the useful or essential information for carrying out the work.

- Less time for discussion and sharing (e.g. lack of team meetings).

- Greater difficulty in clarifying everyone’s mandates and roles.

- Little listening or empathy for the staff’s concerns (e.g. request for time off, needs in organization of work).

- Tensions, conflicts or rudeness not managed on the work teams.

Social support from colleagues

Social support from colleagues currently marked by:

- Greater instability on the work teams.

- Fewer or lack of team meetings.

- Greater distance between a healthcare professional and the members of her team.

- Lack of informal opportunities to meet, exchange, share and help each other.

Recognition

With regard to recognition, is the current work situation characterized by:

- Lack of respect and esteem for staff.

- Difficulty in adequately recognizing staff efforts.

- Lack of recognition of the risks incurred by staff.

- Existence of iniquities or favoritism between sectors or individuals.

- Tensions related to remuneration in a context of a pandemic (e.g. premiums, salary improvements).

- The staff’s sense of job security in keeping their jobs and working conditions.

Decision-making autonomy

For decision-making autonomy, can we, for example, see in the healthcare professionals:

- A lack of opportunities to participate in decisions that affect them.

- A lack of opportunities to use their skills and develop new ones.

- Little possibility to show creativity and take initiatives.

Organizational conditions

Certain organizational conditions also affect the work climate and staff’s mental health, including the lack of:

- Team cohesion.

- Planning and organization of work.

- Confidence in colleagues.

- Preparation of the institution.

- Training and equipment for avoiding contamination.

- Psychological support.

Courses of action

Here are a few examples of courses of action whose positive impacts on the staff’s health are widely recognized. Each setting can adapt them based on their reality. This list is not exhaustive, and can be improved according to the psychosocial risk factors specific to each workplace.

Facilitate the exchanges between immediate superiors and staff by establishing communication procedures (e.g. regular team meetings, electronic exchanges)

- Communicate regularly and transparently as to what needs to be done and how to do it.

- Being attentive to staff concerns and suggestions and follow up on them as soon as possible.

- Pay attention to the staff’s issues of work-family balance (e.g. childcare, telework).

Reinforce the culture of support and mutual aid in the workplace

- Lead by example.

- Encourage empathy and compassion on the work teams.

- While respecting the physical distancing measures and using technological tools, provide opportunities for workers to be together, express themselves, help each other and reflect on the solutions for the challenges encountered.

- Pay attention to the conditions conducive to the emergence of psychological harassment at work (e.g. unresolved conflicts, rudeness) and implement, as soon as possible, the necessary measures to prevent it and, if applicable, stop it (see the documentation de la CNESST) (CNESST documents on this subject).

- Equip/give the staff the appropriate means so they can do their work, safely and satisfactorily (e.g. telework tools, personal protective equipment, clear procedures in the event of the presence of symptoms).

- As needed, provide one-off training to acquire the minimum critical knowledge to carry out the work required.

- Encourage the staff to take the full scheduled break.

- Foster daily recognition, reward everyone’s efforts and make a positive assessment of the work.

- Consult the employees about the decisions affecting their work.

- Invest in the participation of people and groups and stimulate initiatives.

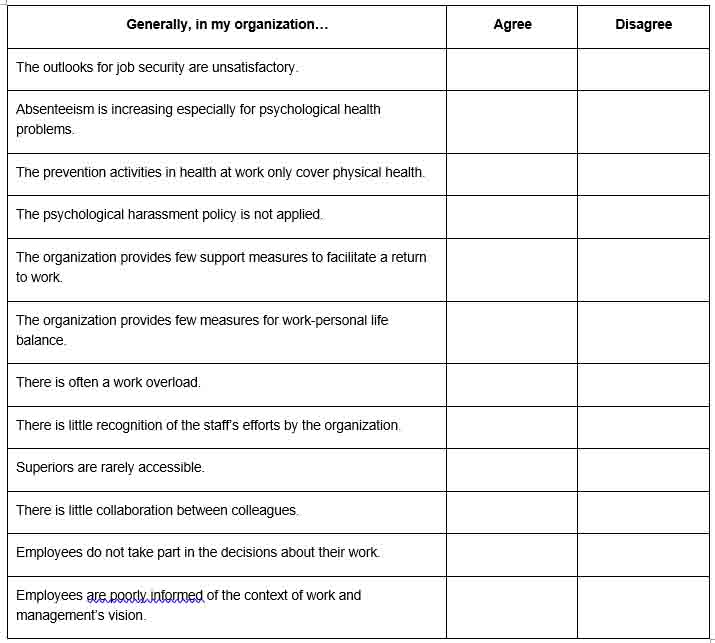

Are there risks in your workplace?

The various stakeholders in the workplace are asked to answer the following short questionnaire, which aims to raise awareness of the preventive measures and organizational constraints that may be harmful to health.

The answers given will provide an initial insight into aspects of work organization and management practices that should undergo a risk assessment. This assessment can be done with the help of the Tool for Identifying Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Workplace developed by the INSPQ.

If you agree with most of these statements, the presence of psychosocial risk factors in the workplace should be assessed. Talk to the OHS officer for your local union.

Strategies for taking care of yourself during the pandemic

Look after essential needs

Healthcare professionals are accustomed to thinking that they have to be available for others and their own needs are secondary, without taking into account the fact that failing to eat or rest causes exhaustion. Be sure to eat, drink and sleep regularly. Not doing so jeopardizes mental and physical health and in the end, it compromises the capacity to care for patients.

Plan a routine outside of work

Try to maintain some of your habits despite the new restrictions imposed by the current context. Explore creative ways for other options at home: daily exercise routines, personal care, reading, communicate with loved ones, etc.

Respect differences

Some people need to talk while others need to be alone. Recognize and respect these differences for your patients, work colleagues and yourself.

Talk with family and loved ones

Talk with loved ones, if possible. They are your support outside the health network. They may be able to give you more support if you share with them. Feeling useful to each other is a protection factor.

Limit exposure to means of communication

Explicit images and disturbing messages will increase your stress and may lower your efficiency and general well-being. Protect yourself psychologically setting limits on the demands that can come from WhatsApp groups or other digital means asking for personal information or advice. Hence, you can preserve your rest time and capacity to get through this endurance race.

Vent your feelings

Professional competence and strength are consistent with feelings of confusion, concern, feeling of a loss of control, fear, guilt, exhaustion, sadness, irritability, desensitization, instability, etc. These feelings are precisely those that make us human. Sharing one’s feelings with someone who inspires safety and trust helps us tolerate these feelings better and resolve them.

Apply recognized emotional management strategies

Breathing, awareness techniques, physical exercise, among other things, may be useful in defusing negative thoughts, emotions and physical symptoms.

Take a break

When possible, take part in activities that are comforting, fun or relaxing for you. Listening to music, reading a book or talking to a friend may help. Some people may feel guilty not working all the time or if they take the time to relax when so many are suffering. However, taking a break will also help in giving better care to patients.

Talk with work colleagues

Talk with your work colleagues and support each other. Isolation due to the pandemic may produce fear and anxiety. Talk about your experience and listen to that of others.

Share constructive information

Talk to your colleagues clearly and encourage them. Identify errors and failures constructively in order to be able to correct them. They all complement each other: praise can be a powerful motivator and stress reducing. Share your frustrations and solutions. Problem solving is a professional aptitude that provides a feeling of accomplishment even for little incidents.

Keep your skills up to date

Rely on trusted sources of knowledge. Participate in meetings to keep informed of the situation and find out what is planned.

.

Allow yourself to ask for help

Recognizing our signs of stress, asking for help and learning to stop to take care of oneself is an internal regulation mechanism that fosters stability in a situation of enduring stress.

Self-observation of feelings and perceptions

Feeling unpleasant emotions is not a threat: it is our mind’s normal defence mechanism when faced with danger. However, be watchful that symptoms of depression and anxiety do not develop: lingering sadness, difficulty sleeping, invasive memories, despair. Talk with your colleagues, superiors, or seek professional help if necessary.

Remember that just because it’s possible doesn’t mean it is bound to happen

Healthcare professionals are constantly exposed to the darker side of this dramatic pandemic: suffering and death in terrible conditions. Obviously, it can create an emotional charge that makes you think of the worst. However, it is important not to lose hope and remember that many of the infected people develop milder forms of the disease.

Acknowledge your team

Remember that, despite the obstacles and frustrations, you are on a great mission: providing care to those in need. Recognize your colleagues, formally and informally. Remember that all those currently working in care settings are doing their best and are the real heroes for the population.

Available resources

- Getting better…my way

- Aller mieux en contexte de pandémie (COVID-19)

- Suicide Prevention Centre: 1 866 APPELLE (1 866 277-3553)

- Deuil en raison de la pandémie (COVID-19)

- Guide pour les personnes endeuillées en période de pandémie

- Ligne d’information du gouvernement du Québec, destinée à la population, sur la COVID19 : 1 877 644-4545

- Physician

- Pharmacist

- Employee assistance program

- Service de consultation psychosociale Info-Social : 811

Not surprisingly, the public health crisis these last few months has aggravated the existing physical health risks in the healthcare professionals’ workplaces. At the forefront, there is of course the biological risks caused by COVID-19 in the workplaces.

The care context in which our healthcare professionals work, already difficult before the declaration of a public health emergency, has deteriorated because of the pandemic and increased the work overload imposed on them. For many of them, the pandemic shock has caused changes in their environment and organization of work.

These changes, imposed by ministerial orders and introduced in urgency and confusion, have weakened individual and organizational defence mechanisms countering the risks related to occupational health and safety. The biological risk caused by COVID-19 in our workplace has in turn caused physical and ergonomic risks. In addition to biological risk, which acted as a catalyst, physical and ergonomic risks were combined.